Some of the earliest known medical devices were being used in dental procedures between 7,500-9000 years ago in a Neolithic farming community from the Mehrgarh site (Indus Valley) in what is today, western Pakistan. Excavations of the site’s graveyard point to a 1,500-year-old farming community employing a long tradition of early dental techniques, as specifically observed in the molars of 9 adults from the area.[i] Flint-tipped bow drills used in early enamel drilling techniques consisted of assemblages of bone, shell, calcite, turquoise, lapis[ii], and other stones.

Medical devices are products or equipment intended generally for medical use. [iii] Whilst there were no regulations governing the use of Neolithic dental tools, full oversight of the medical device industry was only realized in 1976 in the U.S. and 1990 in Europe. We are seeing notable changes to the regulation of Europe´s multi-billion-dollar medical technology sector today, as it transitions from being regulated under the current medical devices directives to two new, complementary regulations.

The era of modern pharmaceutical regulation can be usefully dated from the Thalidomide disaster[iv] in the late 1950s, marking a watershed moment for modern testing requirements for medicinal products in Europe and the US. The widespread use and approval of Thalidomide to treat morning sickness in pregnant women in many European countries resulted in a dramatic increase in children born with birth defects and malformed limbs. The total number of people affected by Thalidomide use during pregnancy is estimated at 10,000, and 40% of the infants died around the time of birth [v] and most before turning one year old. This level of harm to public health highlighted the need for stricter regulations and the need to adequately test and communicate the risks of medications. A flood of new pharmaceutical regulations followed, requiring manufacturers to demonstrate that their products were safe and effective before they could enter the market.

For most people, medical devices radically improve the quality of life and even save lives. However, malfunctioning devices have also caused significant harm to a number of patients over the last decade. Medical device adverse events are unexpected events that occur during or after a patient comes into contact with a medical device. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an adverse event as “a problem that can or does result in permanent impairment, injury or death to the patient or the user.”[vi] One example is the Poly Implant Prothese (PIP) case where unapproved industrial-grade silicone was used for breast implants, instead of medical-grade silicone. The scandal affected about 300,000 women in as many as 65 countries. [vii] The case exposed vulnerabilities in the medical device regulatory sector and consequently, the European Commission evaluated standards and processes to propose a stricter framework to protect public health. Thus, the new regulations aim to provide an optimized, uniform system, with a greater focus on product safety, quality, and performance.

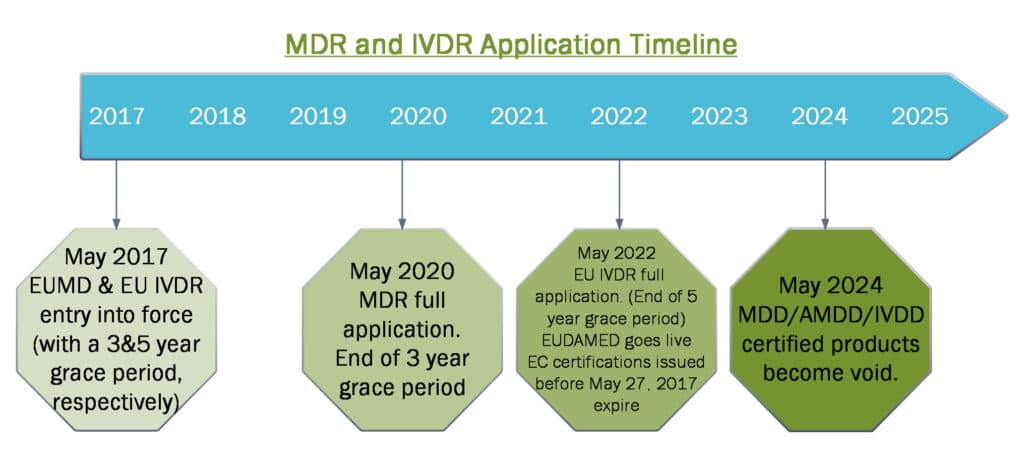

Existing legislation on Medical Devices and active implantable medical devices ( EU Directives (93/42/EEC, 98/79/EC ) is being replaced by the MDR (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices and the IVDR (EU) 2017/746 for in-vitro diagnostic medical devices entered into force in May 2017 and have a staggered transitional period.

Some of the most notable changes brought about by the EU MDR/IVDR are;

- Stricter approval and manufacturing requirements, and the introduction of traceability and market surveillance requirements.

- Products are being re-classified using a risk-based approach, and elevated clinical testing requirements apply.

- Expanded UDI, serialization and post-market surveillance requirements in the EU market.

- Greater involvement of and increased workload for notified bodies who are struggling to keep up; MDR has reclassified many devices to higher risk and these will all require notified body review. Adding to this challenge is the complex and time-consuming path to accreditation for notified bodies. Slow progress has experts concerned that there will not be enough NBs designated by the MDR’s date application on 26 May, which may result in device shortages on the market.

- The integration of a centralized multipurpose database (EUDAMED).

- The provision of legal certainty for producers, manufacturers, distributors, and importers in the EU market.

Both the Medical Device and the IVD sectors face a significant challenge to plan for and complete before May 2020 and May 2022 to fully comply. The transition from conforming with the current Directive to meeting the new requirements calls for diligent preparation and substantial changes in quality management systems ahead of additional notified body review and inspection.

Author: Lara Bartlett Manager, Digital Communications

Do you need support in understanding how the regulatory requirements affect your Medical Device? Or in ensuring that your medical device design and development are in compliance with the applicable regulations? Or do you just want a check and update of your Quality Management System? KVALITO is a strategic partner and global quality and compliance services provider and network for regulated industries. To learn more about our service please visit us on www.kvalito.ch

If you would like to benefit from KVALITO’s expert services, feel free to contact us or us an email to contact@kvalito.ch.

References:

[i] “Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry” A. Coppa et al, NATURE|Vol 440|6 April 2006, ©2006 Nature Publishing Group

[ii] . Kenoyer, J. M. & Vidale, M. in Material Issues in Art and Archaeology III(eds Vandiver, P. B., Druzik, J. R., Wheeler, G. S. & Freestone, I. C.) 495–518 (Material Research Society, Pittsburgh, 1992)

[iii] https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/medical-devices retrieved on 4.2.2020

[iv] COGLIANESE, CARY, editor. Achieving Regulatory Excellence. Brookings Institution Press, 2017. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt1hfr226. Accessed 22 Feb. 2020.

[v] Miller, Marylin T. (1991). “Thalidomide Embryopathy: A Model for the Study of Congenital Incomitant Horizontal Strabismus”. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 81: 623–674. PMC 1298636. PMID 1808819.

[vi] World Health Organization. Medical Device Regulations: Global Overview and Guiding Principles. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

[vii] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-court-france-implants/women-with-defective-french-breast-implants-may-claim-damages-only-in-france-eu-court-adviser-idUSKBN2001HS Women with defective French breast implants may claim damages only in France: EU court adviser Marine Strauss